On a cool October morning, two men crouch down near a chain link fence along Melnea Cass Boulevard and make a deal. One of the men, younger, perhaps in his late 20s, rolls up the left sleeve of his fleece coat while the other thumbs through a handful of cash before stuffing it into his jacket pocket. Cars bustle past along the street.

About a dozen yards away, Domingos DaRosa, a Roxbury native and community activist, walks through the grass between the sidewalk and the fence, his eyes scanning the ground for hypodermic needles. He’s wearing steel-toed boots and white latex gloves, and he carries a small red box with a clear plastic lid and an opening to drop the needles through. He picks up 10 needles in the first minute of his patrol.

The younger man, his head covered by a New England Patriots beanie, prepares to inject drugs nearby, and the other stands up and looks around. DaRosa approaches, following the trail of needles as he picks them up one by one.

“Be careful guys,” DaRosa says to the men as he picks up a Poland Springs water bottle filled with used syringes. “There’s a bad batch going around.”

The older man nods and reaches into his pockets. DaRosa steps closer and holds open the red box as the man drops two needles inside.

This is all routine for DaRosa and others in the community trying to keep as many needles off the ground as they can. They walk through city parks and playgrounds, under overpasses and along sidewalks, picking up what they see and emptying their full boxes into red kiosks scattered across the area for needles to be safely deposited.

DaRosa said he first noticed a problem with discarded needles about eight years ago. Since then, he said, the issue has skyrocketed.

311 data from the City of Boston corroborates this, showing that the number of requests for needle pick-ups has steadily increased over the past five years –– now totaling over 17,000. The needles are but a quantifier of a bigger problem, a numerable proxy for a larger issue: the nation’s opioid crisis.

DaRosa continues on his way, picking up more needles. Some are hidden beneath leaves that have fallen from the tree branches overhead. Others have the needle either bent or broken off, a sign of a conscious effort made by people suffering from drug addiction, DaRosa says, to mitigate the spread of disease.

He also picks up empty Narcan dispensers, the medication used to treat narcotic overdoses. “Any time you see these,” DaRosa says, “that means someone was brought back to life.”

Residents Respond

Aside from DaRosa, other Boston residents have also started exploring the issue. Andrew Brand, a computer professional and South End resident who lives along Massachusetts Avenue, has started exploring the 311 data on his own in an attempt to make sense of the issue.

Brand said his interest in the needle collection data began as a way for him to practice creating graphics and studying the opioid crisis. Brand sought hard data, rather than anecdotal evidence, to show that the effects of the opioid epidemic are heightened in Roxbury and the South End, and that more needles are typically found in these areas.

311 requests for needle collection show what he expected to be true –– that there is a higher concentration of calls coming from those two neighborhoods than elsewhere.

Each dot represents a 311 needle pickup request, and the dark red dots represent higher density of requests.

The data itself has its limitations, though, Brand said.

To begin with, the needles are only one quantifiable dimension of the opioid crisis. Further, the data doesn’t show how many used needles are actually on the streets –– it only reflects the calls made to request their removal.

“The needles are really one aspect of the problem. They’re the only (quantifiable) aspect of the problem that I have access to,” Brand said. “Really, I want the neighborhood to be cleaned up and go back to the way it was, which was sort of a normal neighborhood, albeit one next to the hospitals. It always had its share of homeless people, but they didn’t really cause any quality of life problems for the neighborhood.”

Brand isn’t the only Boston resident who’s had enough.

Jennifer, another South End resident who asked to only be identified by her first name, had her first close call with used needles in the spring of 2018. While playing with her son in Southwest Corridor Park, she noticed him bending towards something. As he went to grab it, she recognized the tell-tale clear syringe and pulled him away before he could pick up the used needle.

Though that was the only needle her now 3-year-old has nearly grasped, Jennifer said she sees discarded syringes around Boston and in parks and playgrounds, on a weekly basis.

The problem has become so severe, she said, that she now only allows her son to play in indoor areas, or takes him to museums or suburban parks. She has also started exploring possible solutions for the community at-large to deal with discarded needles and the effects of the opioid crisis.

“I’m just a mom. I’m not an opioid expert, but clearly, the city is looking for solutions,” Jennifer said. “No one knows what to do, so I do have a list of things.”

Among her ideas for possible solutions are distributing retractable needles rather than standard syringes, and making them brightly colored so pedestrians can easily spot them and dispose of them.

After the incident with her son, Jennifer called the Boston Public Health Commission’s needle exchange and was unsettled to find that they are not exchanging needles but rather distributing them without requiring an exchange. As long as they are giving out syringes, she said, they might as well be making them easier for the general public to identify and discard.

As a first-time parent, Jennifer said she worries during the day that her son will be stuck by a needle while playing. At night, she worries that her husband, a surgeon at Boston Medical Center on Massachusetts Avenue –– part of an area otherwise known as the Methadone Mile –– isn’t safe when he leaves work.

To Jennifer’s family, the side effects of the opioid crisis have become too much to sustain. They are now actively seeking to relocate outside of Boston.

“The city is being taken over,” Jennifer said. “If you were to have asked me four years ago if I wanted to raise my son in the city, I would say 100%. I love the city, I’m an extroverted person, I enjoy community, but now we’re actively looking to get out of the city for the sole reason of the drug-using community … It’s just too much at this point.”

“I’m just a mom. I’m not an opioid expert,but clearly, the city is

looking for solutions.”

In October 2014, the bridge to the Long Island Recovery Campus was closed and torn down due to safety concerns. For years, the campus was a place where people struggling with addiction could go for shelter and recovery services.

In the years since access was cut off, community members in Roxbury and the South End have noticed a growing presence of drug abuse in their neighborhoods, along with more needles littering the ground.

But service providers, who help people suffering from addiction every day, say this epidemic isn’t anything new.

“It’s new to people who weren’t really paying attention to the problem at the time, and now that it’s all here in one spot, you can’t not pay attention to it,” said Mario Chaparo, program director for the engagement center and outreach services at the Boston Public Health Commission.

“When it’s somebody that they know or somebody that they’re really close to, then they understand and they might ask ‘How can I help them?’ It’s sad to say, but most times it has to touch somebody in their own life for them to get it and realize we need to do something more.”

One of BPHC’s main priorities is mitigating the spread of disease that can occur when people share and reuse needles. To combat this issue, the department gives out clean needles, as well as other items such as sterile wipes, toothpaste, soap and feminine hygiene products. While the program is called a needle exchange, people can still get clean needles without turning in used ones.

‘I would give out as many needles as someone needs for them to not get a disease.’

Some have criticized this strategy, arguing that the program is only putting more needles out into the community. But Chaparo says the department collects more syringes –– whether they are turned in or picked up off the ground –– than it hands out. He estimated that his team collects some 200 to 250 needles every day.

“I would give out as many needles as someone needs for them to not get a disease,” he said. “Anywhere that someone is dropping a needle, of course (we’re concerned) if someone gets stuck. But when we think about the bigger picture –– you know, I just heard on the news about a new strain of HIV. There’s new strains of Hepatitis C, there’s all these new things that have come in. I’d rather keep giving out needles to lessen that harm.”

Chaparo said his department also distributes small containers for people to place their used syringes in, like the red box DaRosa carries with him when he’s collecting needles off the ground. When the box fills up, it is turned in to the department in exchange for more clean needles.

Another strategy has been the placement of large red kiosks around the city for depositing needles safely.

This move has also drawn criticism, particularly with two kiosks placed near the Orchard Gardens K-8 School, which sits a short walk from the intersection of Melnea Cass Boulevard and Massachusetts Avenue.

Jennifer, for one, said the kiosks aren’t the answer –– especially not when placed in front of schools.

“Putting something like that next to a school, that’s not the solution,” Jennifer said. “It’s like saying a person who’s drunk is going to pick up all their stuff. They’re just not in the frame of mind.”

‘We’ve always been here’

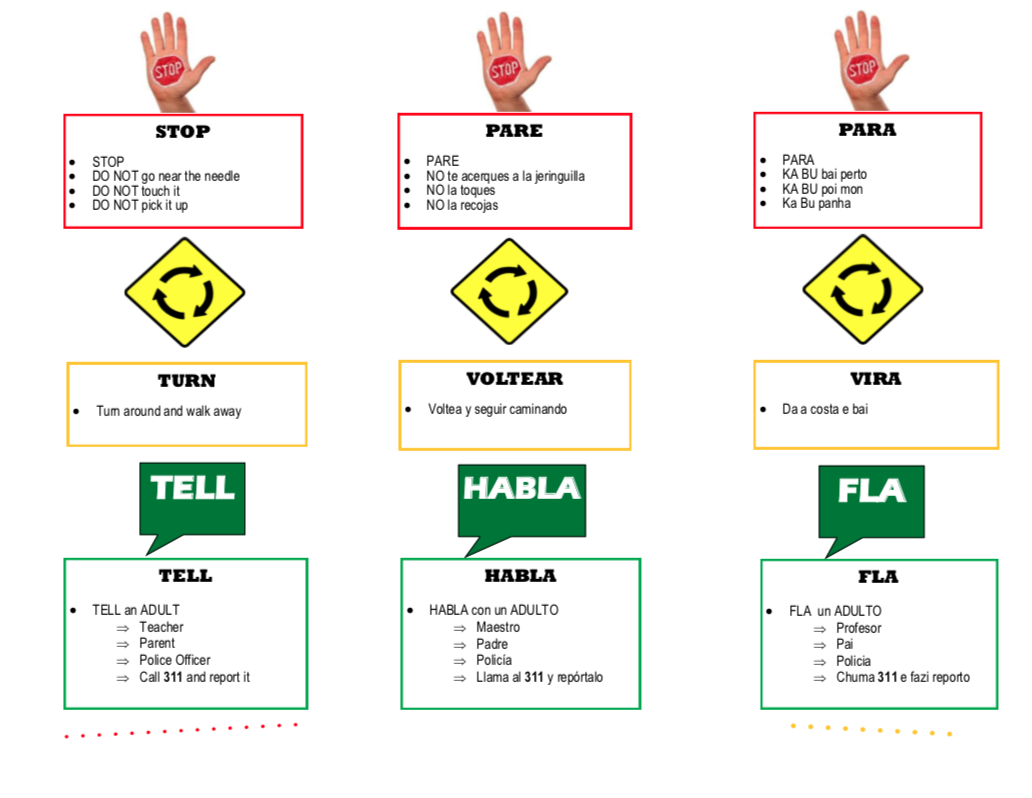

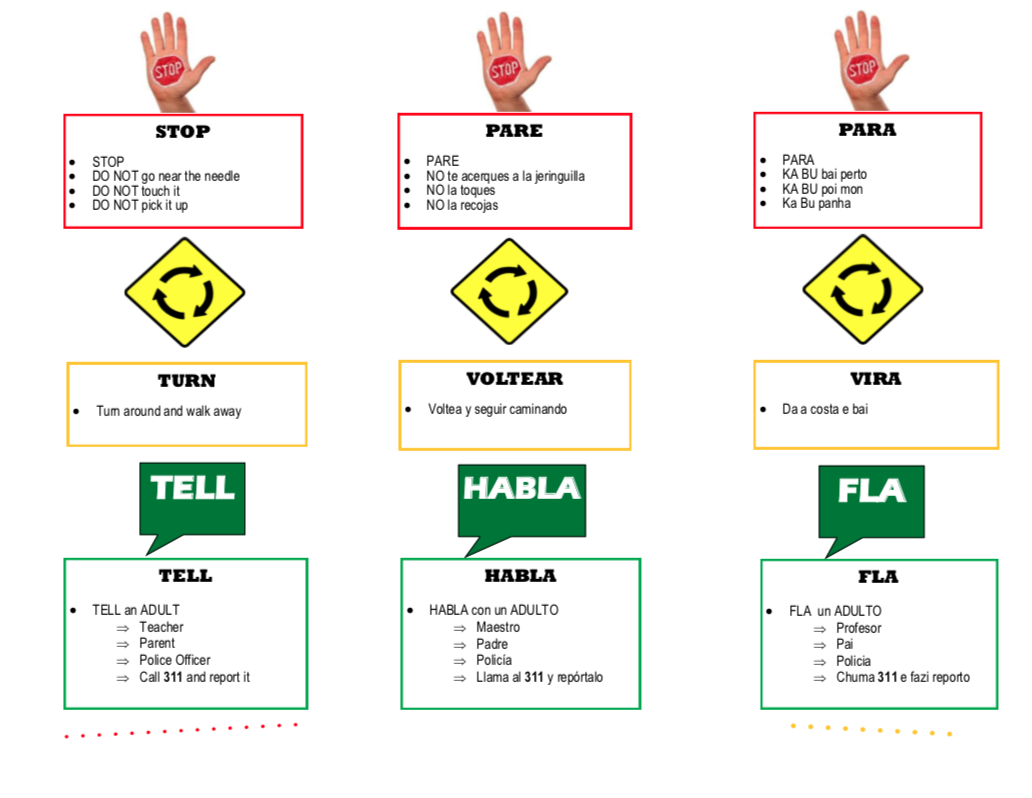

The Orchard Gardens School has been dealing with the issue of littered needles for at least the past four years. In 2015, school nurse Sue Burchill designed a brochure to hand out to students in the K-8 school explaining what to do when they see a needle on the ground.

“You learn to stop, drop and roll in school when there’s a fire,” she said in a recent interview. “Our brochure says ‘If you see a needle, stop, turn and tell an adult. If there’s no adults, call 311.’”

The key point is for children to not pick up the needle themselves, but Burchill said she believes the kiosks encourage students to do precisely that.

The brochure is written in three languages. The school has nearly 1,000 children, she said, and about 75% are learning English as a second language.

“We started the brochure and have been educating the students since 2015,” said Burchill, a lifelong Boston resident. “We’ve gone to the mayor, we’ve gone to representatives in the neighborhood, we’ve stood outside on the sidewalk on Melnea Cass and Albany (Street) with signs. Nobody seemed to care until the South End community, the wealthy physicians and such, as needles started coming their way, that’s when they started paying attention. That was in 2017.”

“We don’t really have a voice,” she later added. “We are here, and we’ve always been here.”

“We don’t really have a voice”

311 data shows a high concentration of calls for needle pick-ups coming from the area surrounding the school, which sits near the intersection of Melnea Cass Boulevard and Massachusetts Avenue. Custodians walk the school grounds each morning checking for needles and other drug-related litter before students arrive, Burchill said.

One day last fall, she said several hundred pill capsules were discovered on the kindergarten playground. In November 2018, a boy was pricked by a needle during recess. Burchill said he had to undergo testing to rule out any infections and is okay.

‘Well, it’s not adorable. It’s sickening.’

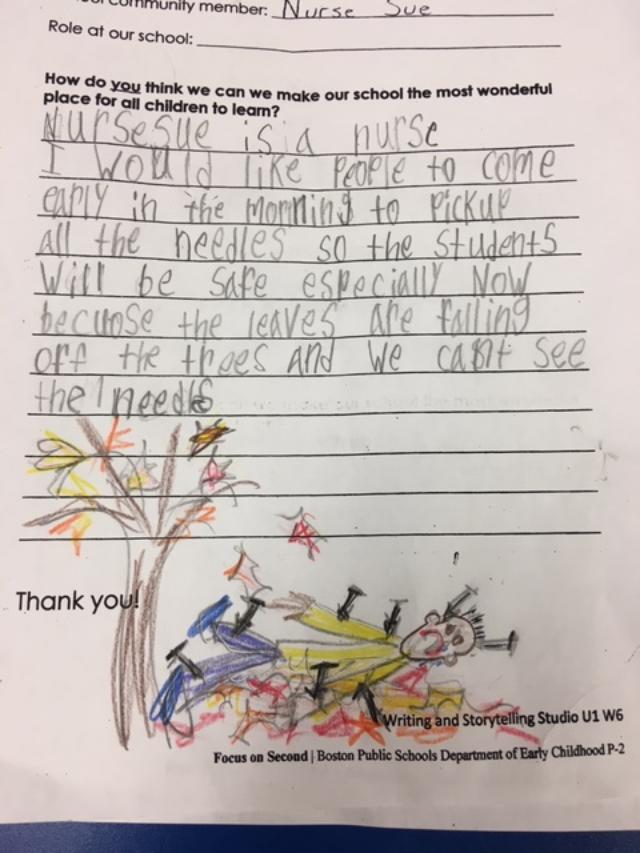

A short time later, a class of students was asked how the school could be made safer. The students responded in words and pictures. One student drew a picture of a boy in a yellow shirt and blue pants laying in a pile of leaves with several needles stuck to his body.

The student wrote, “I would like people to come early in the morning to pick up all the needles so the students will be safe especially now because the leaves are falling off the trees and we can’t see the needles.”

“It’s adorable,” Burchill said. “Well, it’s not adorable. It’s sickening.”

DaRosa, too, is concerned with children being exposed to drug use in public, as they step over needles and other litter on their way to and from school.

As he stood on Melnea Cass that October morning and watched the man in the Patriots hat inject the drugs into his arm, DaRosa shook his head.

“If the kids are seeing it, what do you think their outcome is going to be in life?” he said. “This is not normal.”

Back to the Scope